10 Secrets of The Last Judgement by Michelangelo

The gloom and terror of The Last Judgment come as a tremendous shock after the beauty of the Sistine Chapel Ceiling. The change is symptomatic of the

transformation which had come over Rome itself after the dreadful events of the Sack of Rome in 1527 and its aftermath, from which the center of Christendom did not recover for many years.

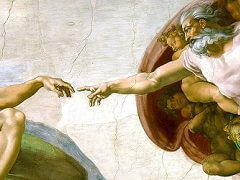

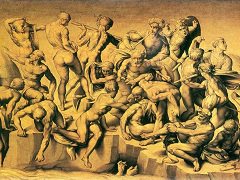

The space directly above the altar is reserved for the mouth of Hell, into which the celebrant of the Mass frequently could look as he performed the sacred ritual. To the left of Hell Mouth

extends what little of the earth has not yet been dissolved, and from its barren ground, reminiscent of the earth on which Adam lies in the Creation of Adam,

the dead crawl out of their graves. Some are well preserved, some skeletons, in conformity with a tradition appearing in the monumental form in Signorelli's great Last Judgment series in the

Cathedral at Orvieto, which Michelangelo must have studied with much interest.

Throughout the Last Judgment, the dominant color is that of human flesh against the slaty blue sky, with only a few touches of brilliant drapery to echo faintly the splendors of the

Sistine Ceiling. The dead rising from their graves still preserve the colors of the earth - dun, ocher, drab. A few patches of red appear in the angels' cloaks. The whole section, moreover,

has darkened considerably from the smoke of the candles at the altar.

10 Secrets of The Last Judgement by Michelangelo

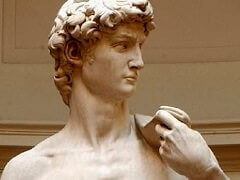

1. Art historians generally agree that Michelangelo included his own self-portrait in his busy "The Last Judgement" fresco, pointing to the skin held by St. Bartholomew, which they believe

has the artist's face. St. Bartholomew was one Jesus' 12 disciples. On his later travels as a missionary, he was flayed alive.

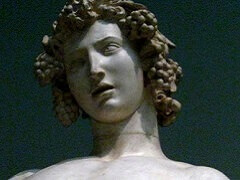

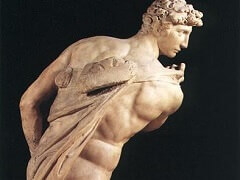

2. In keeping with the precedent set by earlier Renaissance artists, Michelangelo included figures from Greek mythology in his Christian-inspired The Last Judgement". Such mythic figures

as Charon, who rowed souls down the river Styx to Hades and Minos of Crete, who served as one of a trio of judges in Hades, according to Dante's "Inferno," share wall space with the likes of Jesus,

Mary, saints and angels.

3. One legend surrounding the fresco says that the artist portrayed Biagio de Cesena as a serpent-wrapped Minos after the Vatican dignitary vocally criticized the unfinished painting.

Because it contained mostly nude figures, Cesena claimed "The Last Judgement" was more fit for a tavern than the Sistine Chapel. Interestingly, recent cleaning of the fresco reveals a serpent

biting Minos' genitals.

4. Just a few weeks prior to Michelangelo's death, scandalized churchmen at the Council of Trent agreed to engage artist Daniele da Volterra to add clothing to the nude figures in

Michelangelo's fresco.

5. Approximately 25,000 people per day currently view The Last Judgement in the Sistine Chapel.

6. "The Last Judgement" was massive, measuring approximately 39 feet by 45 feet. In comparison, The Last Supper

fresco by Leonardo da Vinci was approximately 15 feet by 29 feet.

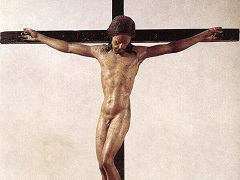

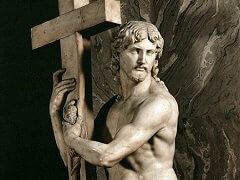

7. Some of the ways Michelangelo took artistic license with the biblical story include his beardless Christ, the omission of Christ's throne and his host of wingless angels. In fact, just

after the artist's death, Giovanni Andrea Gillio collected all Michelangelo's departures from the biblical tradition in a book entitled "Due Dialogi."

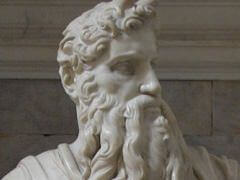

8. Other existing artworks had to be demolished to make way for "The Last Judgement," including "The Assumption of Mary" by Renaissance artist Pietro Perugino and two of Michelangelo's own

earlier works, the "Ancestors of Christ" lunettes. Portions of Perugino's Moses and "Adoration of the Kings" cycles were also covered by the fresco.

9. The descending figures in "The Last Judgement" may correspond to the seven deadly sins, according to one school of thought. For example, one tumbling figure carries keys and coins,

representing greed.

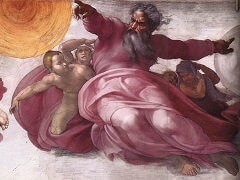

10. The golden aura surrounding Christ and Mary at the center of the fresco may be a reference to Apollo, Greek god of the sun, and Christ's rotating arms suggest the circular motion of the

heavens as well as the cycle of life, death, and resurrection.