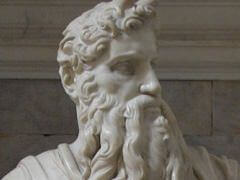

Moses, by Michelangelo

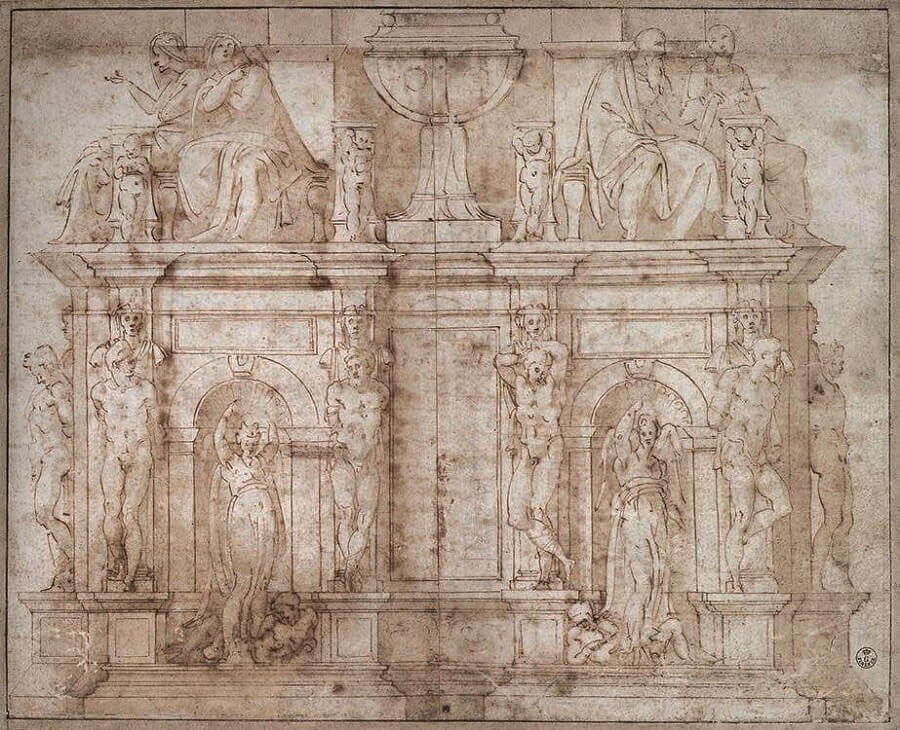

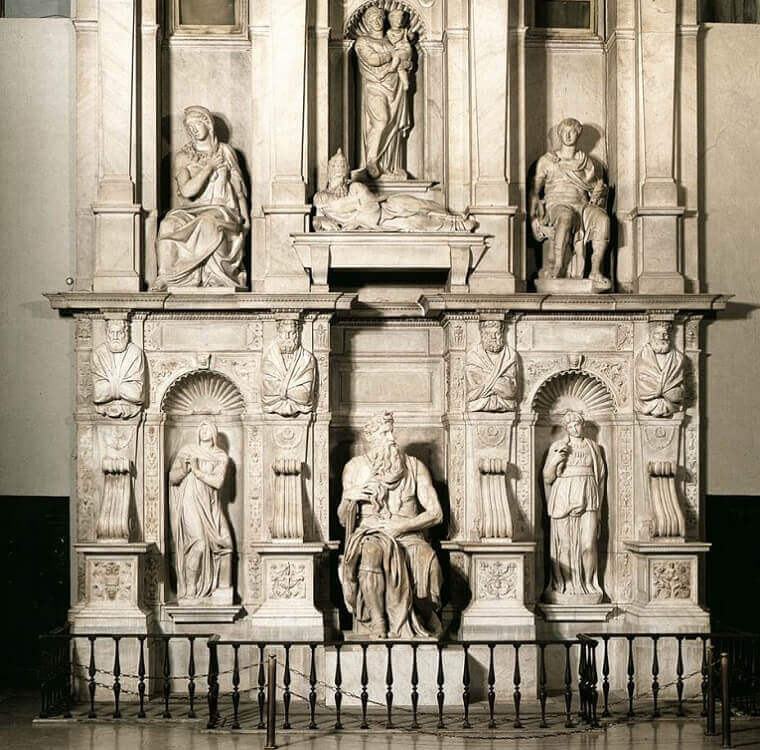

The statue of Moses is the summary of the entire monument, planned but never fully realized as the tomb of Julius II. It was intended for one of the six colossal figures that crowned the tomb. Elder brother to the Sistine Prophets, the Moses is also an image of Michelangelo's own aspirations, a figure in de Tolnay's words, "trembling with indignation, having mastered the explosion of his wrath". Conceived for the second tier of the tomb, the statue was meant to be seen from below and not as it is displayed today at eye-level.

The figure of the biblical Lawmaker, which had been a part of the overall project since 1505, has survived in a copy of a drawing now in Berlin, and like the Saint Paul, Active Life and Contemplative Life he was to occupy one of the corners of the upper story. He was also to have occupied a high niche position in the 1513 project. His final position was, however, in the central arch of the wall monument in San Pietro in Vincoli, assuming an unplanned hegemonic role and - to his disadvantage - situated lower down, where the sculptor's efforts to balance out the proportions through perspective foreshortening are lost.

Twice life-sized, the Moses is a unique masterpiece of Renaissance statuary and art in general. It is believed that Michelangelo was alluding to this very same statue when he wrote, on 16 June 1515, "I have to work very hard this summer to finish this work quickly". The truth of the matter is that the statue remained in the room in Via Macel de' Corvi for almost thirty years, until it was installed in the church between 1542 and 1545, where it became the fulcrum of the monument to Julius II, a rather reduced version as compared to the original project. Most of the work was carved to a finished state, although some of the less visible parts, such as the neck, the back of the head and the seat, are rough.

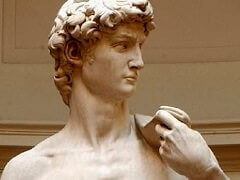

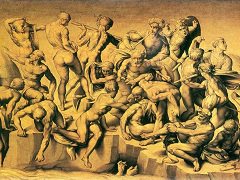

Moses is seated, clad in a tunic, leggings and sandals alluding to biblical antiquity, and his legs are wrapped in a heavy cloak that cascades down to fill the space between his knees. His right foot is firmly set forwards on the ground, while his left foot is retracted and precariously balanced on the edge of the sculpture plinth; the pose is unstable perhaps to suggest that the figure is about to rise. With the torso in a frontal position the head sharply turns to look left. Both hands are occupied with the flowing, wavy ropes of Moses' long beard: the left hand grabs at the ends of the curls, the right moves the central mass over as if caught in it, at the same time holding still up against his side the two tablets of the Ten Commandments.

From the top of his head, amidst the deep volutes of curly locks, two horns emerge from a striated surface, an allusion to the two beams of superhuman light that emanated from Moses when he came down from Mount Sinai. Situated behind the Moses are two relief slabs of unequal quality - now visible only in photographs - that represent two giants holding up a coat of arms.

Since the 19th century, there has been a series of critical comments on the statue that have interpreted its features (moreover, already interpreted in two very different ways by the two biographers of his time!) in light of the most varied and not necessarily warranted interpretations. It was viewed in light of Savonarolian thought as an allegory for the papacy, as a self-portrait or projection of Michelangelo, as a cosmic being comprising the four elements. His frown and heedful expression have been justified as his reaction to seeing the Jewish people make offerings to the bronze serpent. A 19th-century psychological interpretation of his mien paved the road for Sigmund Freud who, in his essay Der Moses des Michelangelo analyzed the artist's rendering of the Bible character in terms of an exceptional and rational power of self-control over the passions, considering it the image of a hero of spirituality, ready to sacrifice his individual affective life to defend the fate of the Jewish people.