Architect by Michelangelo

As we have already seen, Michelangelo was a brilliant artist; but he was more: he was a total artist. Two periods of his life were

devoted primarily to architectural structures in the two places where he spent his time, Florence and Rome. It was probably not a

field where the artist could venture authoritatively. And yet, in keeping with his general vision of art and form, Michelangelo

conceived, in his early period, an architecture that bears the imprint of his expressive will; then in his later years in Rome, he realized

projects whose spatial conception profoundly changed the art of construction.

Michelangelo's first important architectural project was the fagade of the church of San Lorenzo, a commission from Pope

Leo X de' Medici, who wanted to honor his family. In a project design competition, the Pope and Cardinal Julius de' Medici

chose Michelangelo's design over those presented by the most prominent artists of the time. Baccio d'Angelo, Michelangelo's

assistant on this project, build a model based on this design. It was rejected. A new model built by Michelangelo and

Pietro Urbano won the Pope's approval two years later; unfortunately, the work was interrupted and was never completed.

An analysis of successive projects for the fagade reveals a progressive simplification of the structure; the pedestal of the

pilasters of the upper story is organically linked to the building. On Giuliano da Sangallo' model for the project for the same

building, which was inspired by antique monuments, Michelangelo projected the massive attic story on a ground level support of the

light columns. In this way, he could create a bold relationship of contrasting energies, of opposite rhythms where the tension of

the structure is manifested in the classic appearance of the whole.

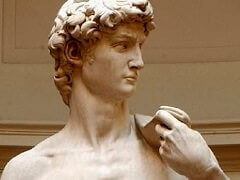

This first project was conceived by a sculptor. The ten

figures of the fagade were to be placed at the intersections between the verticals and horizontals. It is likely that Michelangelo's

first commissions, consisting of ornamenting structures already built, facilitated the possibility of breaking the classic, organic

harmony between the internal structure of buildings and their faithful reproduction on the facade. Thus, he was the first to conceive

of the independence between the interior and exterior, believing the exterior to have a public ornamental function.

The second important commission given to Michelangelo, following the accession of Clement VII de' Medici to the papal throne,

concerned the erection of the Laurentian Library adjacent to the Cloister of San Lorenzo. The year 1524 was devoted to the

preparatory studies. From August 1524 to 1534, Michelangelo supervised the work. The Library was finished in 1560 by Ammannati.

As functional architecture, the Library breaks with the only model of religious or official structures, which was revolutionary for

the time. A place for retreat and meditation, which would also serve to house the collections of manuscripts and books of the Medici

family, the Laurentian Library is above all, in Michelangelo's conception, a spiritual space. The entrance vestibule is conceived as

a meditation between the exterior and interior, which prepares the visitor for the austerity of the reference rooms. According to

his general principle, Michelangelo applied his sense of the organic interdependence of the parts to the whole in his architecture.

The reading room, immense in width, has bays of desks on the two sides of a central corridor. The walls are composed of pilasters

whose restraint contributes to the impression of the room's austerity. Between the pilasters, there are frames without ornamentation.

This austere architecture, sometimes judged monotonous, corresponds, in fact, to Michelangelo's concern to free the spirit of the place

reserved for meditation.

The absence of decorative elements, except for the ceiling, which is ornamented with antique motifs, is a complete departure from all

the Florentine principles of construction, but will soon become a model repeated in the erection of public buildings of the Cinquecento.

The staircase at the entrance of the Library is in itself a remarkable piece. Here, Michelangelo breaks with the purely functional

aspect of that element to incorporate it as an entirely separate architectural piece in the imposing volume of the vestibule, which at

the same time is reduced to serving as a stairwell. This monumental staircase, which will later serve as a model in baroque architecture,

is composed of a series of steps divided by two banisters in the center. Two angular lateral staircases surround the central staircase

of convex steps. The landings of the lateral staircases open at a right angle onto the central staircase, which seems to be an

architectural aberration, where only the ornamental intent guided the master. The three staircases lead to the same center door at

the top of a central axis.

Besides the construction of this prestigious building, Michelangelo was to realize or plan architectural works of lesser importance.

Thus, in 1532, Clement VII asked the artist to work on a gallery destined for the preservation of the relics for the church of San

Lorenzo, and as we have seen, Michelangelo was for a time occupied with the realization of Florentine fortifications against the risk

of invasion.

These fortifications change from top to bottom the data for these specific constructions as we restore the plans preserved at the

Casa Buonarroti. For the first time, the builder thinks as much about defense as offense, from the interior towards the exterior,

achieved by spaces with a clear view, placed between the bastions in the form of pliers or claws which enclose the uncovered areas.

As de Tolnay noted, the plans for the fortifications would have a decided influence on one of the greatest architects of strategic

construction, Vauban.

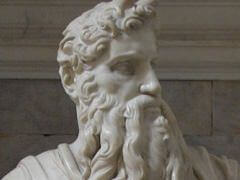

During a period of about twenty years, Michelangelo ceased all activity of an architectural nature to devote himself to numerous

commissions for sculpting and painting; yet from 1546 to the end of his days architecture occupied more and more of his attention.

Despite their autonomy and their true originality, the architectural conceptions of Michelangelo were linked in the early period to

the heritage of Giuliano da Sangallo and in the second period of those of Antonio da Sangallo, the Younger, a number of whose works,

Michelangelo would finish. The two major works that would mobilize all the attention of the artist's old age concerned the

commissions of Paul III, who wanted to establish Roman supremacy by the reconstructions of St. Peter's and the Campidoglio.

Of course, these projects were finished after the artist's death, but the numerous preserved plans and sketches prove that they

were completed in accordance with the architect's wishes.

The splendor occasioned by the visit of Charles V to the Eternal City anticipated the replanning of the Piazza Campidoglio. Because

of a lack of finances, it was not until 1539 that the Senate, following the will of Paul III, appropriated the first funds for the

construction, whose care was soon entrusted to Michelangelo. The first problem was to create harmony and an organic place between

the two buildings, the Palazzo Senatorio and the Palazzo Conservatori, from different aspects around the antique equestrian statue

of Marcus Aurelius, placed in the center of the Piazza from 1538, and whose pedestal Michelangelo reshaped in an oval to lighten the

statue itself and then to harmonize it with the new oval plans for the Piazza. Michelangelo's first concern was to plan the

unification of the facades, to make them symmetrii cal, by creating a new building, which would close the Piazza, the fourth side

consisting of a t staircase, assuring passage between the Campidoglio and the city. The general plan of the Piazza is composed of a

central oval representing the caput mundi surrounded by an open base ; trapezoid with the balustrade of the staircase. Here is an

extraordinary theatricalization of the space, consisting of a center towards which the star shaped design of the Piazza converges. The

facades of the Palaces represent the tension of embedded monumental forces. Horizontals and verticals fit together violently in the

form of Ionic columns and Corinthian pilasters that give an age-old character to the whole of the setting.

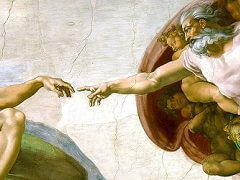

The reconstruction of St. Peter's had already been envisaged by Julius II; a contest was then organized, and Michelangelo's rival,

Bramante, emerged the victor.

Before his death, Bramante only realized the beginnings of the construction and Raphael succeeded him, proposing new plans. Upon his

death, Antonio da Sangallo, the Younger, assumed the direction of the work, as chief architect. In 1546, he died and Michelangelo became

the master of Roman architecture and resumed Bramante's initial plan. Around four central interior columns, Michelangelo created a

simple structure in the form of a Greek cross, as Bramante had planned, but simplifying the different successive projects of his

predecessors. The central structure is in the shape of a square, open on one side to form a portico of six columns supporting a

triangular pediment. Michelangelo had studied the model of the cupola of the Duomo in Florence from which he conceived the soaring

dome that overhangs the structure. Faithful to its traditional conception, Michelangelo, for this church, the greatest in all

Christianity, created a bond of contradictory forces linked together in the unity of the symbolic heightening of the dome. While a

building of small proportions had already been constructed by Antonio da Sangallo, the Younger, Paul III declared a competition open

to the greatest architects of the time for the construction of the largest private palace in Rome, the Palazzo Farnese, for the

Pope's son, Pier Luigi Farnese. Michelangelo won the commission. It is recognized today that the part attributed to Buonarroti is

relatively modest, Sangallo's plans having prevailed. However, Michelangelo constructed the cornice of the building and it is

remarkable. At its summit it accentuates the whole of the building and unifies it like a frame that contains the structure. In the

center of the building, the first floor, the work of Sangallo, is broken by a balustrade that dominates the door of the building.

This addition by Michelangelo, as well as the coat of arms over the center window, adds some life to the facade, which is relatively austere.

The Palazzo Farnese completed, Michelangelo, near the end of his life, realized several more building plans, such as the church of San Giovanni

dei Fiorentini, a religious structure which was supposed to be built between the Via Giulia and the Tiber, in the heart of the Florentine quarter

of Rome. Plans have also survived for the conversion of the Diocletian Baths into a church called Santa Maria degli Angeli. Sketches by the

master concerning the commission for the Sforza Chapel in Santa Maria Maggiore, and the Porta Pia have also been preserved. The architectural

work of Michelangelo cannot be separated from the entirety of his artistic problematics. In the same way, two fundamental lines are apparent,

which inscribe the artist's own genius in this field. First, his capacity to synthesize elements borrowed from the past, then, his will to produce

a powerful work. Forceful and massive architecture, Michelangelo's construction is symbolic; each element is significant in its totality and the

direction of a spiritual and cosmic project.