Rondanini Pieta, by Michelangelo

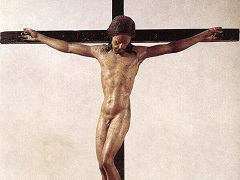

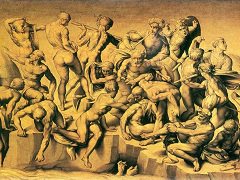

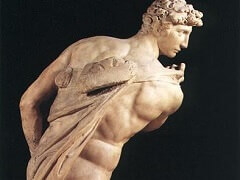

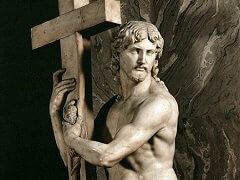

Like the other Pieta, this is a work for which Michelangelo was the sole patron. The considerable changes made to the sculpture by the very hand of the author, which it would be too reductive to call pentimenti in that they constitute actual changes in design, have left us with a group that we might liken to a "palimpsest", where at least two variations in conflict with each other are present. A first idea and consequent sculpted version includes an athletic figure of a naked, deceased Christ, supported upright by the shoulders by a man wearing a turban as he lowers him into a depth that should be that of the tomb. The figure supporting him is without the shadow of a doubt a man, also convincingly substantiated by John T. Paoletti, as the short tunic he wears that leaves his left leg naked from the knee down could not have been worn by a woman. Still a part of this first phase are Christ's legs, his incomplete right arm detached from the body, the just roughed out mass of the supporting figure with the upper part of his face turned upwards, which now coincides with the veiled head of the figure itself. We cannot exclude the idea that the first version included three figures. A subsequent phase led to the semi-destruction of the Christ, reduced to a hollowed out torso on which the face with its features just roughed out rests, the sculpture of a second right arm, but this one in a backwards position and up against the other figure, and the transformation of the man into a woman - believed to be the Virgin despite the lack of proof - with the creation of a vaguely feminine veiled head that bends and attempts to touch the dead man's hair in a gesture of sorrowful affection.

Rondanini Pieta offers us a privileged view of Michelangelo's modus operandi. His unprecedented passion amazes us, a passion that would never again be surpassed, evident in the way he treats the marble as something that is forced to surrender to sudden changes in the overall design, if not total changes of heart. By expressing his personal quest - and it could only be thus - "per forza di levare", or "taking away", Michelangelo denied the fullness (despite the fact that it had just been achieved, and with great effort) of an enriched, complete form, to instead search, by way of deliberate impoverishment, for the ever-evasive essence of the concept.