Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci

Michelangelo, Raphael and Leonardo da Vinci were the nucleus of fifteenth-century Florentine art. Also worth citing is the painter and historian

Giorgio Vasari, whose Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors and Architects first came out in 1550, with the enlarged edition appearing in 1568. Lastly, there was Michelangelo's close

friend and first biographer, Ascavio Condivi. Whatever the shortcomings of these two men's works, they provide invaluable insight into the Florentine Renaissance and the people who made it happen.

Michelangelo and Da Vinci stood out as strong and mighty-personalities with two irreconcilably opposed attitudes to art - yet there is a bond of deep understanding between them. Da Vinci was

twenty years Michelangelo's senior and each had his own set vision about art. Their fierce independence led to clashes whenever circumstances, such as simultaneous commissions for cartoons of the

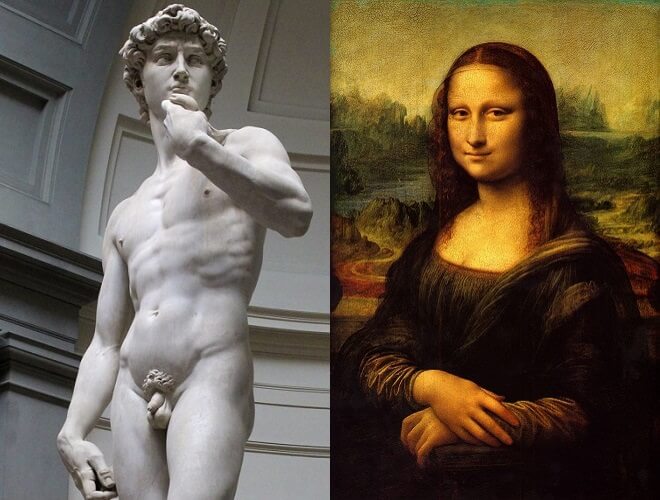

Palazzo Vecchio, brought them face-to-face. From Donatello and Verrocchio, Da Vinci had developed his sfumato style, best defined as "blending light and shadow without trait or sign, like smoke"

and best witnessed in the Mona Lisa at the Louvre Museum of Paris. It obtains hazy contours and dark colours, opposite to

Michelangelo's technique seen in his Doni Tondo (a.k.a. The Holy Family) at the Uffizi in Florence. Da Vinci spent years under Verrocchio while Michelangelo had

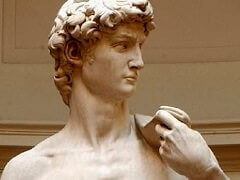

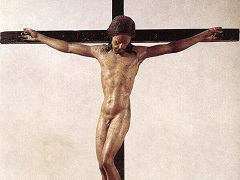

lasted just one at the Ghirlandaio workshop before studying under Bertoldo: Michelangelo saw himself primarily as a man who worked stone.

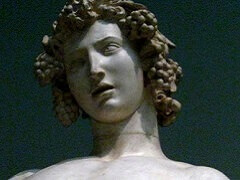

For Da Vinci, the essential concern was the long quest for truth while Michelangelo was dogged all his life by the meaning of art itself. Both had dissected cadavers to learn anatomy but for

different reasons: Da Vinci was out to render the truth of a gesture in order to better represent action and emotion while Michelangelo simply had a hardwired interest in crafting nudes - Da

Vinci never painted nudes. Michelangelo's David standing in contrapposto is the direct result of his anatomical studies. In short, anatomy affected the two greats very differently.

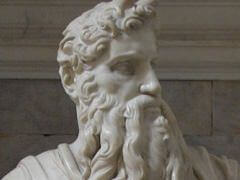

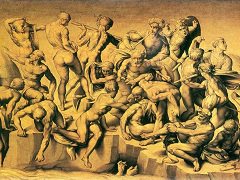

These two rivals both also had a penchant for non finito, the abandonment artworks in progress. Da Vinci would regularly abandon canvasses while Michelangelo would leave off sculptures.

Da Vinci blends non finito into sfumato until they become hard to distinguish while in Michelangelo non finito is only rarer in his paintings. Either Michelangelo abandoned a work because of

pressure from other commissions or he was deliberately toying with a novel form of particularly dynamic and expressive art. After doing a model, he would apply himself erratically to the actual

statue, with hyperactive frenzy powering him through some sessions and cool detachment through others. The fury he hurled at marble would pare away the excess and liberate the stone's soul but

he didn't always follow through; non finito was a spin-off of his exceptional creative talent. Instead of aping his predecessors in Christian figurative painting, he opted to start off in stone.

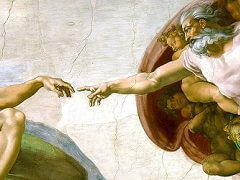

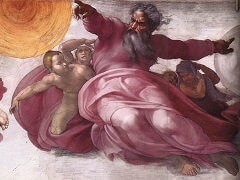

He even painted his Tondo Doni as if it were a work of stone. When Pope Julius II handed him the commission for the Sistine Chapel Ceiling, Bramante,

Raphael Sanzio and other rivals were hoping he would wheedle his way out of it. Yet he made a success of it! In the end, Michelangelo demonstrated excellence

in painting too. When it came to architecture, Michelangelo had amassed the maturity to integrate Bramante's way of empowering buildings with dimensions proportionate to those of the human body.